Shortly after November’s midterm elections, Harold Schaitberger picked up his phone and found an old, friendly voice on the line. It had been three years since the mustachioed president of the International Association of Firefighters union briefly shook Democratic politics by backing his group off its planned endorsement of Hillary Clinton, just in case then–Vice-President Joe Biden decided to get into the 2016 presidential race. Now, with the 2020 contest around the corner, Biden wanted to catch up.

The 40-minute call came just as wildfires devastated swaths of California. Biden wanted to know how he could help, and Schaitberger directed him to the union’s relief effort. Soon after, Biden’s political group emailed supporters asking for donations. When the conversation turned to politics, however, it felt like a reunion. “We joked that we were the only union to endorse him, and he didn’t even announce last time,” said Schaitberger, whose organization’s members ended up voting overwhelmingly for Donald Trump over Clinton, according to its internal polling. The union still has to go through a formal process, he made clear on the phone to Biden, but “I’m pretty confident that if he makes the decision to [run] — which I think will happen right after the first of the year — we will be with him from Day One.”

Biden is 76 years old. He’s either run for president or gotten close six times now, and each experience weighs on him in its own way — from the misery of his aborted 1988 run to the delayed triumph of 2008, to the agony of 2016, when he passed on running in the aftermath of the death of his son. But, say over half a dozen Democrats who’ve spoken with him recently, he’s never been more convinced that he’s the man for our time. As he’s traveled for the last two years, Biden’s made little secret of the fact that he thinks his party, and the nation, made grave errors in 2016 — and that he could repair a lot of the damage if he runs for, and wins, the White House. Calls and meetings like these are the exact kind of reinforcement he’s seeking.

“I said to him in recent times, and two years ago, that had he made the decision to run — and of course you have to win the nomination, but I think that was doable — there’s little question in my mind that if he were the nominee, he’d be the president of the United States right now,” said Schaitberger. “And I think he believes that, too.”

But Biden, of course, has not yet decided to run in 2020, despite the encouragement of political allies and the parade of polls, both public and private, showing him ahead of the rest of the bursting prospective Democratic field, let alone Trump. Instead, the man who’s grown notorious among his friends for taking his time to make big decisions is moving even more deliberately than usual, weighing whether the personal toll of yet another campaign is worth it, for him and for his family, which has endured a brutal few years.

Top potential supporters are left reading the tea leaves: Some days it feels like he’s 75 percent of the way committed to running, some days 25, said one who keeps in touch with him.

If he runs, Biden is sure to face obvious, and potentially devastating, knocks on his record and his age, from the left and from younger candidates — many of whom are convinced his current lead in polling is ephemeral, based only on his fame and not his real viability. He’d be putting his status as the party’s beloved elder statesman — especially in places that aren’t always friendly to Democrats — to the test. And he’d be sacrificing his newly found personal financial comfort, after a lifetime of tight budgets.

So he’s wading, slowly, through what it means to have not a shred of doubt that he’s the right man for the time, but also a real fear that the time is no longer right for him.

When he left the White House in early 2017, Biden has since revealed to friends, he was presented with a four-year, $38 million deal proposal from a speaking agency. Biden, who was out of an elected job for the first time in 47 years, and who still talks with a certain pride about not coming from wealth, rejected it, wary of the 2016 example. Then, Clinton’s lucrative paid speeches became a major point of attack against her both in her primary against Bernie Sanders, and then against Trump. Biden had already made clear to allies that he wanted to be part of the 2020 discussion, and he didn’t want to rule himself out. Not like this. (A Biden aide couldn’t confirm the numbers, but said it was true he had received such offers and turned them down.)

Instead, he embarked on a book tour and agreed to occasional, carefully selected, paid speeches while surrounded by a familiar group of aides and advisers that have been at his side for years, creating a cocoon of relative silence compared to the rumors flying around other potential White House aspirants’ camps. Biden has instructed this team to keep his options open, but not to start building any national operation quite yet.

If Biden were to run, it wouldn’t be as a Barack Obama retread — it’s unclear how much of his former boss’s electoral coalition, or political magic, he’d be able to re-create. While Obama and Biden remain close, prominent members of Obama’s inner orbit for a while seemed more interested in the potential candidacy of former Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick, and the former president himself has said little about Biden’s possible campaign. At least two other members of the Obama administration are still considering runs, even as Biden looms: former attorney general Eric Holder and former Housing secretary Julián Castro. The former president, in other words, is hardly in the Biden-or-bust camp.

Instead, Biden’s plan for steering his party back to presidential power is straightforward: During the midterms he and his team pitched him as the guy who could help win back onetime Democrats who’d drifted toward Trump even while exciting reliable liberal voters who miss Obama, according to party players involved with midterm decision-making. A recent poll circulating in Democratic circles showed Biden leading Trump in a hypothetical matchup in Ohio, the critical midwestern battleground that the president won after Obama took it twice.

A Biden candidacy would likely serve as a flashpoint for Democrats’ central disagreements in the post-Obama, post-Clinton era: Some of his supporters are explicitly talking about it as a chance to win over white working-class voters who swung to Trump, and to reject what they think of as their party’s overreliance on “identity politics” that they fear alienates those voters.

“The Democratic Party has a huge decision to make, and I think the members of our union, and our view of the political environment, speaks to a lot of other working-class, middle-class, middle-of-the-road slices of the electorate,” said Schaitberger. “And I think there’s no question that there is no other candidate that, with sincerity and experience and personal commitment, can speak to that part of the electorate.” To Schaitberger, Biden could answer an existential question for Democrats. “Is the party now going to become fundamentally, and only, a party of identity politics? And — rightfully so — a party of wonderful diversity and colors and ethnicities and lifestyles? Or is it a party that — I would hope — understands that [to win] a presidential election, they’ve still got to succeed in America, fundamentally, between the two coasts?”

A lot of Biden’s critics — and a big part of the Democratic Party — disagree vehemently with this analysis, of course, which is just one part of why they’re concerned about the prospect of Biden 2020. (Bernie Sanders, for one, has made clear to his team that he’s wary of a Biden candidacy; Biden has occasionally taken to throwing quick digs at Sanders into his speeches.) Biden allies are well aware that a primary would likely be bruising, no matter what: He would have to explain his actions during the Anita Hill–Clarence Thomas hearings, for one, and he’d be put on the defensive over his relationship with Delaware’s credit-card industry.

Sanders allies have already projected a willingness to attack his role in passing the 1994 crime bill (“We forget that Bill Clinton and Joe Biden are the fathers of mass incarceration in this country,” said Sanders’s campaign manager Jeff Weaver at Hunter College in October), and others still have pointed to Biden’s penchant for nostalgia as an obvious weakness in a party that’s increasingly young and increasingly diverse. Last year, while campaigning for Doug Jones in Birmingham, Alabama, Biden reminisced about how when he first arrived in the Senate, “the Democratic Party still had seven or eight old-fashioned Democratic segregationists. You’d get up and you’d argue like the devil with them. Then you’d go down and have lunch or dinner together. The political system worked. We were divided on issues, but the political system worked.”

(Responding to that speech, Daily Kos founder Markos Moulitsas told the New Republic at the time, “If Biden’s solution to eight years of Republican obstruction and conservative slash-and-burn tactics against him and Barack Obama is to talk about ‘bipartisanship’ and ‘consensus,’ then he might as well pack up and go home. Because if he’s that stupid to believe that shit, then he’s no longer got any business being in the public face.”)

Possible opponents also believe Biden’s lead in the polls at this early point is largely based on his name recognition compared to the other candidates. He is easily recognized by every Democratic primary voter, but other contenders have not yet had the chance to introduce themselves, or try to knock Biden down. And his age is inescapable, too. Of the possible field, only Sanders is older. No Democrat in the modern era has won the presidency after previously seeking it, and one clear lesson from the 2018 elections was the party’s willingness to reward new faces.

Nonetheless, Biden’s family looms larger for him than any potential political pitfalls — especially since the 2015 death of his son, Beau, say people who’ve discussed his considerations with him. Biden is still recovering from Beau’s death from cancer, and his other son, Hunter, closed a divorce last year, as tabloids reported his new relationship with Beau’s widow.

Biden’s family has been supportive of his runs in the past (his brother, Frank, was tweeting articles about Joe 2020 as recently as late last year; he’s since locked his account), but the prospect of a brutal, personal battle against Trump is still a painful one. It’s already stopped one potential candidate from running: Patrick bowed out last week, citing how “the cruelty of our election process would ultimately splash back on people whom [his wife] Diane and I love, but who hadn’t signed up for the journey.” And then there’s the fact that Biden, for the first time in his life, is now financially comfortable after signing his reported $8 million book deal last year, and taking in money from occasional speaking engagements.

Yet Biden’s made one thing clear to anyone who’ll listen: He still thinks he’s the man for the job, as he spelled out in plain terms at a book event in Missoula, Montana, last week. “I’ll be as straight with you as I can,” he said. “I think I’m the most qualified person in the country to be president.” And he keeps hearing from some longtime allies that he’s the most qualified to pull the country together, too. “I’ve made that same very strong case to him last time when he was considering — that there was only one person who could bring our nation together, who could remind us we’re Americans before we’re Republicans or Democrats, and we have a shared value set,” said former South Carolina legislator James Smith, who ran unsuccessfully for governor in 2018 at Biden’s urging.

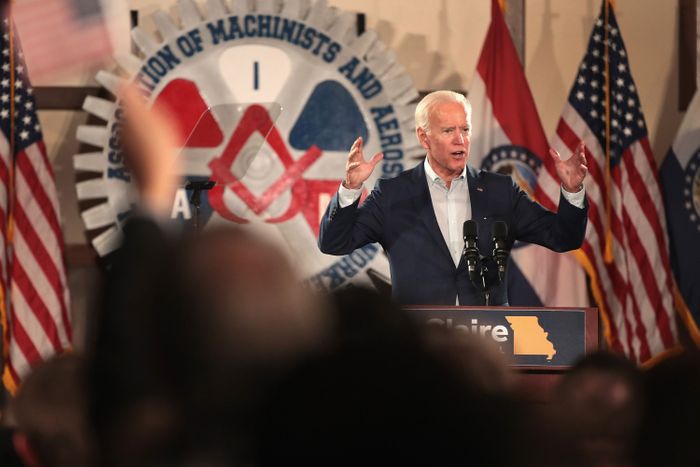

Biden acknowledges that he’d be the oldest-ever president, but brushes aside concerns that he might no longer be up for the job. His allies bristle when it’s pointed out to them that he ended up campaigning a lot, but less than expected, for others in the home stretch of 2018. Unlike Obama, Biden has relished playing a major public role in the age of Trump, extending his book tour for over a year and holding more 2018 campaign events and candidate fundraisers than just about any other major Democratic figure. He’s used this schedule — these speeches, rallies, and interviews — to try to solidify what he sees as his role as Democrats’ top public counterweight to Trump.

He also thinks the dynamics this cycle are different from any other, so dismisses concerns that he’s never gotten very far when he’s tried running for president in the past. Still, in private, he occasionally recites his aphorism — “in politics, you’re either on your way up, or your way down” — and makes clear to allies that he doesn’t want to do anything that could set him on a path down. He’s concerned that if he runs and loses in the primary, that’s exactly what would happen, and he’d find himself sidelined during the general election, as he felt he was in 2016. “That’s got to be part of your thinking, especially at his age,” said one former Biden aide who keeps in touch with his circle. Nonetheless, Biden’s often noted that he’s experienced real loss in his life, and it’s not political loss that concerns him. His aides have yet to pull together a national or early-voting state staffing, or finance plan, believing that those pieces will be easier for him to pull together than for an average candidate.

Biden, who’s never been a fundraising dynamo, has still spent significant time wooing his party’s major financiers in recent months, though — his team acknowledges behind the scenes that even if he wouldn’t need as much money to start as lesser-known contenders, the new primary calendar in 2020 — heavy with expensive states up front — may necessitate a serious financial operation before long. (It could turn into a “huge struggle,” said the former aide, if he doesn’t hit the ground running.) Biden’s met with scores of prospective donors in the last two years, often handing them copies of books that have stuck with him recently, including White Working Class by Joan C. Williams, The Soul of America by Jon Meacham, and How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt. In the 2018 election cycle, he raised (and spent) over $2 million through his American Possibilities PAC, and federal filings reviewed by New York show that the group’s brought in cash from a who’s who of major contributors, including, but not limited to: Hollywood executive Jeffrey Katzenberg; director Steven Spielberg; hedge-fund manager Jim Simons; entrepreneur Tim Gill; investor Jim Chanos; venture capitalist Chris Sacca; entrepreneur Sean Parker; investor Ron Conway; Philip Munger, the son of Warren Buffett’s business partner Charles Munger; real-estate investor Mel Heifetz; and former HP executive and 2010 California GOP gubernatorial candidate Meg Whitman.

And he’s keeping them close. Biden’s backers and supporters last week received invitations to a holiday reception he’s hosting in Washington on December 12, according to an invitation obtained by New York.

His inner circle, meanwhile, hasn’t changed: He still consults Ted Kaufman, his longtime adviser and briefly his successor in the Senate, and political consultant Mike Donilon on almost every decision; Steve Ricchetti, his old chief of staff, is in the room, too. Greg Schultz, a longtime political aide, is responsible for helming the political group Biden launched to help Democrats in the midterms and lay basic groundwork for a potential campaign. Biden’s sister, Valerie Biden Owens, is in on the conversations. The former vice-president keeps in touch informally with a handful of other former senior aides who are tasked with regularly checking in with a slightly larger orbit of supporters.

He’s kept top political allies, like Schaitberger, in the loop on his thinking, as well, though he hasn’t done the kind of outreach to potential influential activist supporters in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada as other possible candidates have since November. It’s not that he isn’t paying attention to what’s going on there, though — he resisted traveling to Iowa or New Hampshire during the midterms for fear of drawing too much attention to his potential 2020 plans, and away from candidates, until the very end, when Iowa congressional candidate Abby Finkenauer’s team asked for his help. He’d been following her race closely, and agreed to swoop into Cedar Rapids. It’s also that he doesn’t think he needs to: In some of those states, he has a network of backers ready to spring to action if called upon. In South Carolina, for example, his top would-be lieutenants keep in regular touch, said Smith.

And yet, every day that Biden doesn’t send a public signal about what he’s planning in 2020, some of his supporters grow more concerned that he’s going to keep putting it off. Already, multiple major backers have met recently with other potential candidates, including Montana governor Steve Bullock. Some have spoken highly of Ohio senator Sherrod Brown and Minnesota senator Amy Klobuchar as appealing options, if Biden doesn’t make a move.

For some, the worry is that his timeline will slip, and that he may decide to wait past the first quarter of 2019, to avoid the inevitable flurry of coverage about Q1 fundraising and endorsements. “He’s told everybody to be ready,” said one informal adviser. But, said that Democrat, “‘Be ready’ doesn’t necessarily mean he’s going to run.”

Biden used to say out loud that he’d decide whether to run by the end of the year. Before too long, he started telling friends he’d decide around January 1st. When he visited Iowa this fall, he told locals he’d make a decision only after the holidays, said Bret Nilles, the Linn County Democratic Party chairman. Now, his closest associates expect him to at least talk with his family about it when he’s with them over the holidays, if not make a final decision.

“In 2015, there was not only personal politics, but there was the reality: the path to victory, does it make sense? The political considerations? The money? This time, that’s not where it is, at all. It’s a gut check, personal decision,” said the adviser.

Last week, in Missoula, he said he’d decide in six weeks to two months.

“We’re at the point where he’s just going to have to make a decision.”